|

Chapter 5

Son ~ Nicholas

When John was only three years old, a baby

brother joined the Ware household.

It was August 12, 1739, and both James and Agnes Ware were 25 years old. As with all of his siblings,

Nicholas was born in Gloucester County. In later years however, as a lot of

his family relocated to Kentucky, Nicholas would be the one son to put his roots

down in South Carolina after the Revolutionary War.

According to T. E. Campbell in his book titled

Colonial Caroline, A History of Caroline County, Virginia, Nicholas was “listed as a Lieutenant

in the Militia in the year 1762, but he eventually reached the rank of Colonel.”

It was also in 1762 that Nicholas (age 23) married Martha Hodges, affectionately

called Peggy.

(Ref. 629, 959, 1062) The

couple

would have eight

children during their 25 years of marriage:

(1) James,

(2)

Frances, (3)

Nancy, (4)

William, (5)

Thomas, (6)

Elizabeth, (7) Edmund P., and (8)

Nathaniel.

Military record

(1) James

- Peggy delivered

their first child in Virginia in

1763. They named him

James, probably after his grandfather. Sadly, he only lived two years and

died in 1765.

(2)

Frances – The will of Nicholas lists this daughter,

Frances (born 1766), and also lets us know

that her husband was George Wilder.

(Ref. Will)

Marriage record

(3) Nancy - Two

years after the death of her firstborn, Peggy delivered a daughter named Ann -

usually called Nancy. Born in 1767, in Gloucester County,

Nancy was healthy enough to not only survive infancy, but eventually live to the

ripe old age of 89. By the time

Nancy married James Hodges in 1786, the family had moved to South Carolina. According to family researcher Dale

Grissom, “in Nancy Ware Hodges’

application to receive a pension as the widow of a Revolutionary soldier, James

Hodges, she tells of the family moving from VA. to S.C.”

(Ref. Grissom)

It was actually in South

Carolina that Nancy first met James L.

Hodges, a man nine years her senior.

James’ parents, Richard and Elizabeth, had moved to the area earlier and they

“lived near Mulberry Creek.”

(Ref. 2548) Family lore holds that when patriarch Richard “was a

Revolutionary soldier and while at home on furlough, his cabin was attacked by

Indians, and he was killed. The legend continued that the Indians captured four

Hodges daughters, bound them securely and put them inside the cabin which they

prepared to burn. However, an Indian warrior was attracted to one daughter,

Dorothy, released her and took her with him, while the others perished in the

flames. . . .

Many

years later, Dorothy Hodges and her Indian son returned for a visit on her

promise, the story went, that she would

return to her Indian husband in Alabama territory. She yielded to pleadings of

relatives to remain and eventually married. . . .

Her son attended the neighborhood school, but in his late teens went back

to his father.” (Ref. 2548)

The

loss of his father and siblings must have had a great effect on James.

Showing outstanding patriotism, he “served several

different enlistments in the Revolutionary War” before he and Nancy wed.

(Ref. 2548)

Marriage records

The

newlyweds started immediately on their own family and provided 11 grandchildren

for Nicholas and Peggy.

1.

Thompson Hodges (born 1786) married twice.

His first wife was Mahala Hill.

On June 24, 1826, Thompson was ordained a deacon in the Walnut Grove

Baptist Church. After losing his

first spouse and moving to Alabama, he married a second time to Catherine S.

Morgan on November 12, 1857.

Thompson died around 1867 in Alabama

2. Elizabeth Jones Hodges (born

March 25, 1788) died December 4, 1872

3. Mary Hodges (born May 5, 1790)

4. John Hodges born (March 24,

1792)

5. James Hodges (born July 1794)

died after 1837 in Mississippi.

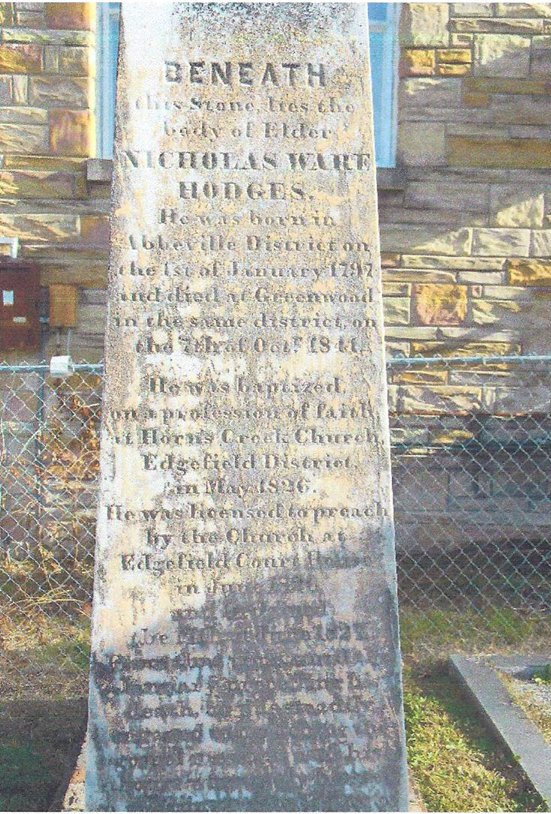

6. Nicholas Ware Hodges (born

January 1, 1797) died on October 7, 1841.

7. Rueben Hodges (born July 23,

1799) died around 1870 in Mississippi.

8. Mahala Hodges (born April

1801) died in 1817 at age 16.

9. Martha Hodges (born April 2,

1803)

10. Nathaniel Ware Hodges (born February 20, 1806)

11. Ezekiel Hodges (born May 28,

1808) died September 1837.

Nancy and James were very active in the Walnut Grove Baptist Church. Both of their names are listed in a

record of the proceedings on the 24th day of June 1826, and the

following list of congregants indicates not only their membership, but that of

their eldest son, Thompson Hodges, as well.

Names of the Members:

Samuel Hill, Nancy Hodges, Richard Gaines, Mary Youngblood, William Graham, Peggy

Henderson, Valentine Young, Dicey Sharp, Thompson Hodges, Jincy

Gaines, Benjamin Rosemond, Robert Gaines, Susanna Roseman, James Hodges, Francis Roseman, William

Hodges, Tabitha Hodges, Jane Huskerson

A newspaper article

written in 1943 described the history of the church as follows:

The "Church at the Walnut Grove on Mulberry

Creek" as it was always described by the clerk, did not show any gain in

membership by the end of its third year. Beginning with eighteen charter

members, it lost within two years two of these by letters of dismission and on

Oct. 20, 1828 Susannah Rosmond died, the first loss by death. This brought the

membership down to fifteen, but the addition of ‘Polly Hodges’, wife of James

Hodges by letter from Turkey Creek about this time, brought the membership up to

sixteen. Then on Jan. 4, 1830 after a sermon by the Rev. Nicholas Ware Hodges,

the first two members [were] received by baptism. These were ‘Polly Hodges,

sister of, and Mahala Hodges, the wife of Thompson Hodges.’ (This made the total

membership eighteen again.) Incidentally, there are three ‘Polly Hodges’ already

noted in the record.”

(Ref. Newspaper)

The ‘Nicholas

Ware Hodges’ mentioned in the article was the sixth child of Nancy and James. According to information from author

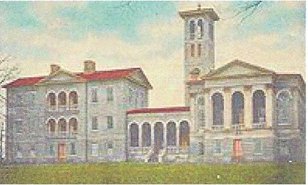

Margaret Watson, Nicholas Ware Hodges “was ordained in 1828 and organized several Baptist churches in upper South Carolina. He was on the committee for Furman

Academy which operated for two years in Edgefield under Baptist auspices, and he

was one of three men named by the State Baptist Convention to select a new site

for the school.” (Ref. 2548)

School seal

Furman Institute

Furman Institute, named for Richard Furman, was one of

the oldest colleges in South Carolina and the 64th oldest in the nation.

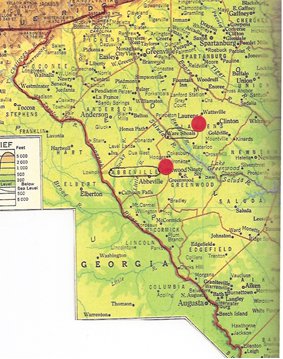

Nicholas was made head of Furman Institute in 1838, but he moved to Greenwood about

two years later and died there. In

1846, when Baptists established a boy’s school in Greenwood, it was named Hodges

Institute in honor of Nicholas. It

has since been torn down.

Hodges Institute, founded by the Baptists and named for the Reverend Nicholas

Ware Hodges, a minister in the area who was active in Baptist education.

A wonderful autobiography of Nicholas Ware

Hodges was kindly provided by Jimmy Rosamond.

It provides remarkable, priceless pieces of information about Nicholas

and all his family. The following

are some excerpts from the work:

AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF NICHOLAS WARE HODGES

“In the 44th year of my age, being confined at home by

protracted illness, from which it is very uncertain whether I may ever recover,

I proceed to the execution of a task, which I have desired and intended for many

years, viz: to write a brief narrative of my life, for the instruction and

benefit of my own children. . . . I

must first gratify a natural curiosity in giving some account of my parentage. My grandfather, Richard Hodges,

emigrated from Virginia, before the Revolutionary war, and settled in Abbeville

District, on Mulberry Creek, then a frontier settlement in the vicinity of the

Cherokee Indians. His wife's maiden

name was Jones. She survived her

husband many years. I can recollect

her when she was nearly a hundred years of age.

My father's name was James

[Hodges].

There being no school established in that

newly settled part of the country, and all that were capable being necessarily

employed in opening the country and reducing it under cultivation, my father had

no opportunity of going to school.

Three days were the most of his schooling.

The deficiency he lamented in [later] life and endeavored to supply it by his

own efforts. He learned to read and

sign his name.

Before the

Commencement of the Colonial dispute (Revolution) my grandfather died, leaving a

widow and twelve children . . . my grandmother was reduced to great suffering. The Indians burned her house and

carried one of her daughters away captive.

She returned home after the war, scarcely able to speak English. My grandmother had to fly for

protection to the woods and shelter herself and children in the hollow of a

large tree.” [This is the

account of Dorothy Hodges written about earlier.]

My father was about 18 years of age

at the commencement of the war and was soon engaged in active scenes. He was not the man that ever shrunk

from danger, where duty or necessity called, and was consequently employed by

his captain, with other daring young men, in several dangerous adventures

against the Tories. . . . In all

these battles, my father never received a single wound, though he never deserted

his post and saw many fall dead on his right hand and on his left. If this was not an evidence of a

special providence I know not where to find any.

After the return of peace, my father married Ann [Nancy Ware],

daughter of Nicholas Ware, who had

emigrated from Virginia and settled on Turkey Creek, Abbeville . . . . My mother's parents [Nicholas and

Peggy Ware] both dying, left under my

father's care their two youngest sons, Edward and Nathaniel A. Ware, at a tender

age. He brought then up as his own

children and gave them the best education which the schools in his reach

afforded. . . .” [For information on Nathaniel Ware, see his section.]

“I was born on Lord's day, 1st Jan 1797 and was the

sixth of eleven children. I was

delicate in appearance and thought not to be equal to the labors of the farm. My uncle selected me from the rest and begged my father to keep me at school until he himself should

finish his education, and he would then educate me, by way of return to my

father for the kindness he had shown to him.

My father did so. . . . One

trait of character early developed itself - that was fondness for reading; but

unfortunately I had no access to suitable books. . . . Having read all I could lay my hands

upon in my father's little library, I at length found an old book with very fine

and dim print. I resolved to know

its contents. It was the Bible. I

commenced at the beginning and read on with increasing interest. I often read by fire-light, after the

rest of the family had retired to rest, and thus early injured my eyes, from

which they never fully recovered.

Very salutary impressions were made on my mind at this age. I saw that God befriended those

patriarchs wherever they were and suffered none to hurt them. I had a great

desire to be like them. I was now

about 12 years of age. In the summer

of 1810, my uncle came to carry me to Abbeville, to commence the study of Latin

with him, whilst he was pursuing the study of law.” Nicholas further writes: “I must stop here to review the scenes

among which I had been brought up - together with their effect on my mind . . . my mother [Nancy Ware] had a great respect for religion, which

she had imbibed from her parents.

[Nicholas and Peggy Ware.]

They were both pious members of the Baptist church on Turkey Creek. She used to reprove her children

about using bad words and indulging passion.

My father was brought up in the Episcopal Church in Virginia, and

certainly had great respect for religion and ministers; but very little for the

church in which he had been brought up.

He often read the Testament and other good books, but said nothing to his

children about doing so. The

Testament, however, was generally used as a school book . . . . I hated Latin because I was to be

made proud by learning and could not become the humble Christian I had desired

since I first read the scriptures, and gave way to grief and melancholy. After some months my uncle entered me

as a student, at Old Cambridge and engaged boarding for me with Mr. Thomas

Chiles.”

Nicholas continued, “After a short stay at my

beloved home, I was carried back to Cambridge, in the beginning of the year

1811. My uncle having made his

arrangements to move to Natchez, Miss., paid me a short visit. He gave me good advice which made an

impression upon me. This was the

last time that I ever had the pleasure of seeing that dear uncle to whom as an

instrument I am indebted for what education I have. I became deeply interested and

prosecuted the study of Latin, Greek and higher English, and succeeded in taking

the prize offered our class. I

remained until the close of the year, 1812.

I spent the year 1813 in reviewing, reading, and instructing my younger

brother and sisters. During the present year, l8l3, my religious impressions

increased. I began to discover my

depravity more and more, and was often in much distress. I made many resolutions, but was

unable to keep them, which destroyed my peace of mind. But, as yet, I knew not the way of

salvation.

In the year, 1814, being about 17 years of

age, I taught a school at Turkey Creek Church and boarded with my Uncle Edmond

Ware, at Scuffletown. I returned to

Cambridge in 1815.

[. . . .]

During the following vacation I occupied a student's cabin alone. Here, happy in my seclusion, I had

much time for meditation and prayer.

I began to reflect seriously upon my situation as a sinner. I had been long striving to obtain

religion, but found myself further off, instead of approaching nearer my object.

[. . . .]

I thought myself the chief of sinners and

was at my wits end. I could make no

greater exertion than I had already made, which had proved abortive. Thus the

lord was stripping me of my self-righteousness; for I had been, for years,

trying to work myself into His favor.”

In closing, Nicholas relayed how, “one Sunday morning I was sitting in my cabin, reading . . . about a man who was in the habit of

cock fighting. Having lost a bet, he

took a solemn oath not to be engaged in such sport. . . . He was, at length, tempted himself .

. . but was struck dead in an instant.

When I read this I closed the book and thought I was as guilty as that

man, for violating so many solemn resolutions.

I looked for the hand of God to be let loose and cut me down. I rushed out of the cabin and sought

the woods. Falling upon my knees I

cried to God for mercy. Tears gushed

from my eyes which afforded some temporary relief. I returned slowly to the cabin with

despair seated at my heart. . . . I

concluded to read again the Epistle of Paul to the Romans. . . . When I came to the 10th chapter, new

views began to be presented. I read,

‘Christ is the end of the law for righteousness to everyone that believeth . . .

the word of faith, which we preach: that if thou shalt confess with thy mouth

the lord Jesus, and shalt believe in thine heart that God raised him from the

dead, thou shalt be saved.’ These

remarkable words arrested my attention.

I thought ‘Is it possible that salvation is placed on such easy terms

merely to believe?’ I had been all

the while under the impression that I must reform and do something to gain the

divine favor. Here was a new

doctrine to me, and I felt ready to lay hold upon it, for every other refuge had

proved a failure. I then asked

myself, ‘Do you believe in the lord Jesus?’

I answered ‘I most certainly do’.

I then began to feel some degree of joy from the thought that there was a

bare possibility for such a sinner as myself to be saved. This joy gradually increased until I

left my cabin to walk in the open fields.

Here as I looked around, all nature seemed to put on a new and more

lovely aspect.”

[You can find the autobiography in its entirety on the web.]

Nicholas was so inspired that he spent the rest of his life preaching the gospel. He married twice. His first wife was Elizabeth (Eliza)

Hughes of Edgefield.

Record

They had two sons, Charles and Edward.

There were more children by his second wife whose name is not known. Nicholas died of tuberculosis at the

age of 44 on October 7, 1841. His

mother, Nancy Ware Hodges, would outlive him by 15 years; dying in 1856

at the age of 89. Nancy’s husband

had also predeceased her in 1828.

“James’ wife, Nancy Ware Hodges, as

his widow, applied for his pension

#W7776. Charlie Hodges sent an

affidavit to support the pension request, March 20, 1846, in which he stated

that James was his brother.”

(Ref. Pension Records)

Grave for Rev. Nicholas Ware Hodges

(4)

William -

In the winter of 1768,

Nicholas and Peggy were expecting another child. Their firstborn,

James, had passed away three years earlier,

and little Nancy had just turned one. October came and went. Finally, on November 1st,

the parents and grandparents (James and Agnes)

welcomed another Ware boy into the world, William

T. Ware. In all likelihood, the letter ‘T’

stood for Grandma Agnes’ maiden name of Todd.

It was a busy year on all fronts.

By 1768, the colonists were feeling the pinch of Great Britain.

Samuel Adams had

circulated a letter opposing the Townshend Acts, a series of laws meant to raise

revenue in the colonies for British benefit.

It was also England’s way of flexing her muscles so it would be known

that she had the right of taxation over her subjects. The action only caused more tension

in the colonies and with English troops (under General Gauge) landing in Boston,

relations were only destined to deteriorate.

Since the war did not come to a complete close until

1768, it makes sense that 15-year old William

would want to be a part of the action.

His entire youth had been spent listening to his family and all colonists

chafing at British rule. Data

compiled by Reverend E. M. Sharp gives proof of his service:

see below

“Available records follow on four of the children of the pioneer Nicholas Ware.

William Ware . . .

a teen-aged soldier in the Revolution, married

Mary Agnew.”

Further

evidence can also be found in

The National Society of the Daughters of the

American Revolution Volume 72 where it states,

“William Ware (1768-1856) is buried in

Pontotoc County, Miss., where his tombstone bears the inscription, ‘A soldier in the Revolution.’ He was

born in Abbeville District, S. C.”

William married

Mary Agnew in 1793 in Abbeville County, and they had the following children:

Marriage record

1. Martha (Patsey) Ware married Charles

Fooshe. She passed away in 1852.

2. Thomas Ware

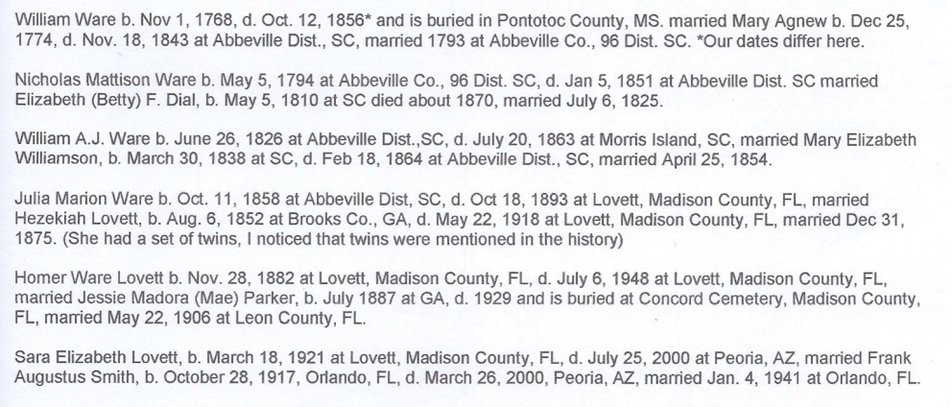

3. Nicholas Mattison Ware (born May 5, 1794) married

Elizabeth (Betty) F. Dial in 1825.

They had a son named William.

Nicholas died in January 1851.

4. Malinda E. Ware married James M. Vandiver.

Marriage record

5.

Martha Ware -

6. James Agnew Ware (born May 12, 1804) married

Harriet Pulliam on August 13, 1828. (For more details of his life, see section marked

below.)

James died April 11, 1865, and is buried in Ware Cemetery, Pontotoc,

Mississippi. below.)

James died April 11, 1865, and is buried in Ware Cemetery, Pontotoc,

Mississippi.

Marriage record

7. Nathaniel Ware -

8. Edmund Ware

-

9. Nancy Ware -

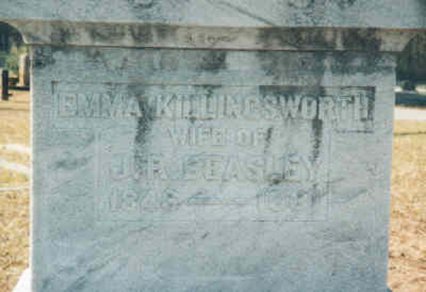

10. Emma Eliza Ware (born in 1813) married

James Franklin Killingsworth in 1887.

She died in 1889.

Marriage record

Grave of Emma Eliza Ware Killingsworth

Nicholas’s

grandson by William, Dr. James Agnew Ware, led an interesting life. Born in 1804, he married Harriet

Pulliam on August 13, 1828. The

couple had the following children:

Priscilla “Priss” Ware (1835); Mariah Ann Hazeltine “Hass” Ware (1836), who

married Sam Weatherall; Mary Agnew Ware (1839), who married James Wilde Crocker

in 1857; William Ware (1841), who died as infant; Margaret Ware (1843); and

Harriet “Hattie” Ware (1871), who wed Sylvanus Lattimore Hearne in 1871.

Grave of Hazeltine Ware

According

to the History and Genealogy of the Hearne Family, S.L. Hearn

“was married in 1871 to Miss Hattie, daughter of Rev. Dr. James A. Ware, a South Carolinian by

birth, who came to Pontotoc county, Miss. at an early day, where he became a

prominent physician and Baptist minister, and one of the county's best citizens.

He and his wife both died there.”

James was not only a doctor, but a dedicated minister as well.

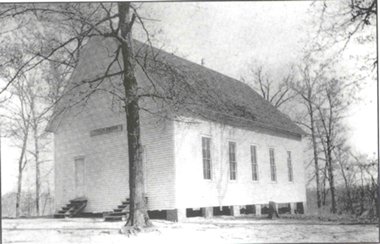

According to Hometown Mississippi, “Toxish Baptist Church was established in

1837 by Rev. James A. Ware of South Carolina.” One of his descendants, Mark

Weatherall, wrote, “Dr. Ware, my maternal

grandfather, was a Baptist minister and was pastor of the Toxish church for

thirty years.”

Photos courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History

-

Toxish Baptist Church

Sign for cemetery

In a recent book titled

The Family Saga: A Collection of Texas Family Legends by Francis Edward

Abernethy, one of James’ descendants submitted a family story of what happened

to Reverend Ware during the Civil War.

Below is an excerpt from the writing of Gloria Counts:

“Acting on a rumor from an escaped slave,

the Yankees demanded to know where Dr. Ware had buried his gold. [He] replied that there was no gold . . .

the Yankees did not believe this.

They took him from the house and hanged

him by the neck several times, up and down, trying to make him tell where he

buried his money. When their torture

proved fruitless, the soldiers finally rode off after taking Dr. Ware’s boots

from his feet and leaving him lying in the snow.

He was never well again, and he died soon after in April 1865.”

(Ref. 2538)

For the full story, see

The Family Saga: A Collection of Texas Family Legends.

William lived a long and prosperous life in South Carolina, expanding his talents to mill work.

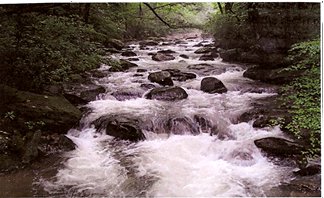

“Ware Shoals is the site of an old water

wheel grist mill operated in the early 19th century by William Ware at Rutledge

Ford, on the Saluda River.”

(Wikipedia)

Like many of his

generation, he used slave labor to manage his large holdings, and according to a

newspaper article printed in 1846, he owned the following 15 slaves:

“Henry, Briss, Fort, Jim, Milly, Nelly,

Ethick, Edmond, Dosh, Mary, Tena, Dicey, Mitchell, Kigh, Wesley. . .”

(Ref. The Banner, Abbeville)

We have recently been able to learn more about

William

Ware through the records of another ancestor, Peggy Smith Kittell. She kindly offered the chart below to

show the family line she follows, coming down from Nicholas’s son – starting

with William.

Lineage from Peggy Smith Kittell

(Ref. 2337)

William’s wife, Mary Agnew Ware, had been

born on Christmas Day in 1774, and she died before William on November 18, 1843. She was 69 years old at her death and

was buried in Turkey Creek Baptist Church Cemetery. William,

who was visiting his son, James Agnew Ware, in Mississippi when he died, was

sadly not able to be buried beside her.

Upon his death on January 12, 1856, at age 88, he was laid to rest in

Pontotoc County, Mississippi.

Grave

for Mary Agnew Ware (wife of William) who was buried in Turkey Creek Baptist

Church Cemetery

(5)

Thomas - Nicholas

and Peggy added another son to the family in

1770, naming him

Thomas Ware. He would marry twice. The two wives were Sarah Gaines and

Nancy Johnson, but there is conflicting data on which one he married first. Most references say that Sarah died

in 1840 and Nancy lived until 1870.

The known children of Thomas are:

Mary Catherine Ware

– born 1810 “She married John Richard Stephens, Jr.

and they had nine children. In 1844,

both John and Mary died in the typhoid epidemic that was raging at the time. John’s parents, John Sr. and Sarah,

left South Carolina where they were living at the time and went to Pontotoc

County, Mississippi to assist in the rearing of the eight orphaned children of

John Richard Stephens Jr. He and his

wife, Mary Ware, a small daughter named Sarah, and a slave had died within a

period of three weeks during a typhoid epidemic.

They were the first persons buried in Cherry Creek

Baptist church

cemetery.”

(Ref.

Stirpes – A Stephens Summary by: Shirley Stephens Martin, September 1996)

The children of John and Mary Catherine Ware Stephens were:

Enoch Monroe Stephens

(1828

– 1899) who wed Mary F. Reeder.

George Washington Stephens

(1829 - 1922) wed Theresa Smith, who died in 1883, and Roenna J.Holditch, who

died in 1940.

George Washington Stephens – grandson of Thomas Ware and great grandson of

Nicholas Ware

Penelope J. (Nelly) Stephens – (1831- 1913) wed Hudson Posey Berry.

John Anderson Stephens - (1833 - 1879) wed Sarah (Sallie) Hitt Ball.

Robert Madison (Matt) Stephens – (1834 - 1888) wed Rachael Elliott Smith.

Mary C. Stephens (1836-1905) wed James “Buff” Smith and James R.

McCarver.

Mary

McCarver – granddaughter of Thomas Ware and great granddaughter of Nicholas

Nancy (Nonnie) A. Stephens

– (1847 - 1925) wed Miles Pegues.

Margaretta Stephens (born unknown date)

William Henry Ware

– born 1820

Perdy (Peregrine)Ware – born 1822

Thomas Jefferson Ware

born 1826

“Thomas

Jefferson Ware, son of Thomas Ware of Abbeville County, S.C. born in Laurens

Co., S.C. 1823 m Frances Malinda Murff 11/14/1852. He migrated to Monroe Co., Miss.

1859, joined the Confederate Army, was captured and died in U.S. Army Prison

Camp at Memphis, Tenn.” (Ref.

Web)

JA Ware born 1832

GN Ware

born 1836

Thomas

Ware lived 83 years and died February 28, 1853.

(Ref. 818)

(6)

Elizabeth - It

was a few years before Nicholas and Peggy had

another baby, but according to church records, they had a little girl named

Elizabeth

(called Bettey or Betsey) on March 22, 1774.

“BETTEY

WARE DAUGHTER OF NICL. WARE

AND MARTHA, HIS WIFE

WAS BORN MARCH 22ND 1774”

Church Minutes

AUG. 12, 1773 THE FOLLOWING INFANTS WAS RECEIVED

INTO THE CARE OF THE CHURCH/

CHLOE SMITH DAUGHTER OF CALEB SMITH...

BETTEY WARE DAUGHTER OF NICL. WARE AND MARTHA/

HIS WIFE WAS BORN MARCH 22ND 1774

(Ref. LIBBIE GRIFFIN TO GLENN GOHR) Broad Run Church minutes

Elizabeth came into a world on the brink of revolution,

and her birth year would mark the convening of the First Continental Congress. (This convention of delegates from

the 13 colonies met to discuss actions that needed to be taken in response to

England’s continued tyranny.) The

Wares could have no way of knowing at this celebration of Elizabeth’s birth that

her father would soon be fighting in a war.

On August

11, 1794, at the age of 20,

Elizabeth

married John Henry Madison. [In the

1700s the name was spelled ‘Mattison’ - it was only later that it was changed to

‘Madison.’] Henry, as he was

known, was the son of Thomas Mattison who came to Carolina from Virginia about

1795, settling in the Pendleton District.

Elizabeth and Henry had four children:

Fielden (born September 9, 1795); Strother (born June 1797); Mahulda

(born July 3, 1799); and Leroy Ware (born in 1802).

Of these children, we know Fielden died very young. The information about his brother,

Strother, has come through one of his descendants.

(See below)

“I now have good evidence that Strother Madison was indeed the

son of Henry (perhaps John Henry) Mattison and Elizabeth Ware who married on 11

August 1794.

Also that Henry was the son of a Thomas Mattison who made

his will in Abbeville Dist. SC on 12 Jan. 1821 with the estate finally being

settled in 1834 after the death of his unnamed wife.

His children listed in the settlement are:

Nevil; Thomas, Jr.; Francis; Jesse; Betsey Mattison

Calvert; Jane Mattison Young; Thomas Davis, Jr. in right of his deceased mother,

Drucilla Mattison Davis; and Henry Mattison's widow,

Elizabeth Mattison, nee Ware.

Henry Mattison pre-deceased his father.

Administration of his estate was given to Elizabeth

Mattison, Thomas Mattison, Sr. (father of Henry) and

Wm. Ware on 29 Oct. 1804

and Elizabeth's brother, Wm. Ware was named

guardian of her three

living children, Strother, Leroy Ware and Mahulda. An older son,

Fielden, born 9 Sept. 1795 is said to have died young.”

(Ref. Ancestry) (Underling done by me)

Strother

married twice. When his first wife,

Elizabeth, died, he remarried in 1824 to Catherine Sample. By the time of his second marriage,

he was 27.

Marriage record for Strother

Madison, Strother Sample, Catherine 13 Jan 1824 Marengo

According

to Ancestry.com, Strother Madison (notice the change in spelling of the last

name), was “born in South Carolina in

1797, married Catherine Sample and they had 10 children. He passed away on 26 Sep 1885 in

Noxubee, Mississippi, USA.” It

is believed that Strother was traveling to Texas with some of his children when

he died. Although there is no

visible gravestone for him at this time, there are cemetery records that show he

was buried in Noxubee County, Mississippi, on September 26, 1885.

Some of the children of

Strother and Catherine Sample Madison were:

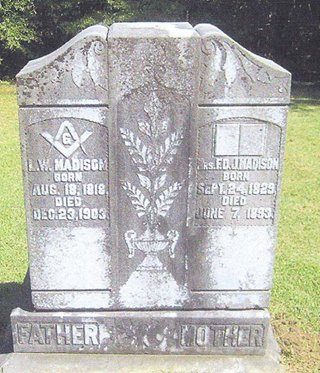

(1) Leroy Ware Madison (1818-1903) from his first marriage; (2) Susan

Madison (1828); (3) William Gaines Madison (1830); (4) James Strother Madison

(1833), who wed Rebecca Barley; (5) Nathaniel Ware Madison (1835), who wed

Cornelia Hawkins on September 24, 1856; (6) Mahulda (Hilda) Madison (1839); (7)

Alexander Madison, and possibly others.

Cemetery for Strother Madison -

Son of John Henry

Madison and Elizabeth "Betsy" Ware of Virginia.

Strother Madison was the husband of Catherine Sample. They lived in

Marengo, Alabama. It is believed that he

was on his way to Texas with some of his children.

We don’t have much information on Elizabeth and Henry’s son, Leroy Ware Madison

(born 1802), but his older brother, Strother, clearly named his first son after

him. Leroy Ware Madison, born on

August 18, 1818, married Frances Deliah Jane Tucker and, according to

Ancestry.com, they had 10 children.

He passed away on December 23, 1903, at the age of 85.

Grave

for Leroy Ware Madison

The only daughter for

Elizabeth and her husband, Henry, was Mahulda

Malinda Madison, who was born on July 3, 1799.

She married Joseph Sample, and the couple lived in Alabama for some time. They had two sons, Henry Alexander

Sample and Leroy Ware Sample. The

couple later moved to Texas where Mahulda died.

She was buried on March 1, 1889, in Marcelina Baptist Church Cemetery.

Mahulda Malinda Madison Sample –

daughter

of Elizabeth Ware Madison

On January 17, 1806,

Elizabeth Ware remarried. Her

second husband, Benjamin Pendleton Gaines, was the son of James Gaines and

Mildred Bland Pollard. According to

one of his descendants, “My grandfather

was Dr. Benjamin Pendleton Gaines - he moved from Virginia to Abbeville Dist

South Carolina and married a Widow, Mrs. Elizabeth Madison, formerly a Miss Ware

. . . . My grandparents had two

sons, Edmund Pollard Gaines who married Susan Sample, and my father, William

Baxter Pendleton Gaines, born 12 Sept 1808.

Dr. Benjamin Pendleton Gaines was a surgeon in the War of 1812.”

Another descendant, Wynell Madison Patton, kindly provides further information: “I'm interested in Benjamin Pendleton Gaines,

born in Virginia. A doctor and

surgeon; he was in the War of 1812 and died at Salisbury NC in 1814. He married Elizabeth Ware Mattison in

1806 in SC, after the death of her first husband Henry Mattison. She had 3 children by Henry Mattison: Strother, Leroy, and Mahulda. Strother Madison is my 3x great

grandfather. She had 2 sons with

Benjamin: Edmund P. and Wm. Baxter

Pendleton Gaines. Strother married

Catherine, a daughter of John Sample. Edmund married Susan, a second daughter of

John Sample. Mahulda married Joseph, a son of John Sample. They lived in Alabama for a while. After the deaths of Catherine,

Edmund, and Joseph; they ended up in Texas.

The other half brother, WBP Gaines; arrived in Texas about 1834 and

fought in the Texas Revolution against Mexico.

He was a lawyer, plantation owner, and legislator in Texas.”

Benjamin was

a physician and surgeon who served in that capacity

during the War of 1812 with the 6th Regiment (Coleman's) Virginia Militia.

He died while in service at Salisbury, North Carolina, in 1814. Elizabeth was a widow again at the age of 40 and

never remarried.

We know the following information about the children of

Elizabeth and Benjamin Gaines:

Edmund Pollard

Gaines (1807-1850) wed Susan N.

Sample in 1828 in Marengo County, Alabama.

They had seven children: (1) William P. Gaines (1830); (2)

Mahulda Gaines (1832); (3) John N. Gaines (1834); (4) Strother Gaines (1835);

(5) Abner Pollard Gaines (1836); (6) Catherine Gaines (1837); and (7) Edmund

Gaines (1842).

By 1860, Susan and some of her children had moved

to Evergreen, Burleson County, Texas, where her brother-in-law William Gaines

had settled.

Susan died in March 1870 in Texas.

William

Baxter Pendleton Gaines

(September 17, 1808 - May 19, 1891)

In an article written by Stephanie

P. Niemeyer for “The Handbook of Texas” we learn much more about William Gaines.

“William Baxter Pendleton Gaines, planter and legislator, was

born on September 17, 1808, in Abbeville, South Carolina, son of Benjamin P. and

Elizabeth (Ware) Gaines.

He taught school in Marengo County, Alabama, until

1832 when he became a merchant in Demopolis, Alabama.

He was approached to enter into a business arrangement in

Texas, and

[in]1835, he established himself in Nacogdoches. By October 1835

Gaines was a wealthy man.

He contributed money to the Texas Revolution and

served as an officer in the volunteer force from Nacogdoches under Gen. Thomas

Rusk that marched to reinforce the siege of Bexar. Gaines acted as

a commissary and quartermaster. After the army

reorganized, Gaines returned to Nacogdoches to serve as deputy paymaster general

of the Texas Army.

[He] left the army to

pursue other opportunities and lived in Galveston while studying law under John B. Jones.

He was admitted to the bar in 1840. In 1842 he moved to Brazoria County with a large number of

slaves and began a cotton and sugar plantation. By 1860 Gaines

had 47 slaves working on his plantation.

In 1846 he joined the United

States Army to fight the Mexican War. He fought with distinction during the

battle of Monterey and was awarded a sword for gallantry.

In 1850 Gaines married Eugenia Gratia Harris of Charlotte,

North Carolina.

They had five children.”

The

Handbook of Texas Online - Article by Stephanie P. Niemeyer

(7) Edmund Pendleton

- On Aug. 16,

1780, Nicholas and Peggy Ware had another

baby boy, Edmund P. Ware. Big sister,

Nancy, was now 13 and baby sister,

Elizabeth,

had just recently turned six. A lot

had happened in the colonies since the birth of Elizabeth. Thomas Jefferson had written the

Declaration of Independence, the 13 colonies had united in their cause for

freedom, an army had been formed under the leadership of General George

Washington, and the French, in 1778, finally declared war against Britain,

making a much needed alliance with the revolutionary forces.

Signing of the Declaration of Independence

It is likely that Peggy saw little of

Nicholas during those years, as he was off fighting in the war. We know

from records kept faithfully by the

Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) that Nicholas was in the Continental Army in South

Carolina. He eventually attained the

rank of colonel.

DAR Military record

The war would not officially be over until 1783, but Nicholas obviously made it home for a visit

sometime earlier because Peggy was soon pregnant again. One can only imagine the concern that

engulfed her during this time, and what a celebration they must have had when

Edmund

Ware was born and the war ended.

Their happiness did not last long, however. Young Edmund’s childhood was cut short with the death of

both of his parents a few years after his birth.

An orphan at the age of seven, he and his younger brother were raised by

their older sister, Nancy, and her husband,

James Hodges. As Nancy’s son,

Reverend Nicholas Ware Hodges, wrote in his autobiography,

“My mother's parents both dying, left under

my father's care their two youngest sons, Edward and Nathaniel A. Ware, at a

tender age. He brought then up as

his own children and gave them the best education which the schools in his reach

afforded.”

(The author confused spelling of Edmund

with Edward.)

Edmund married twice. We know little about his

first wife, Theodocia Nash, because she died shortly into the marriage. We can ascertain from Edmund’s will

that the only child born of this union was Albert N. Ware. In a piece called From Hill To

Dale to Hollow, Ware Shoals, South Carolina, published by a town appointed committee in 1983, we learn “General

Edmund Ware, son of Nicholas and Martha Hodges Ware, married a second wife,

Margaret Gaines, daughter of Thomas Gaines of Newberry County.”

When Edmund remarried, his new wife became a stepmother to Albert, and the

couple added even more to the family.

All in

all, the Edmund Ware family had the following eight children:

(1) Albert Nicholas Ware – born prior to

Edmund’s 2nd marriage

(2) Thomas Edwin Ware – born 1806 (Details of him following)

(3) Nimrod Washington Ware – born 1810. He married Catherine Norwood

and they had six

children. Nimrod died in 1840 in

Louisiana.

(4) Emily Ware – born 1812 and married James

S. Rogers

(5) Peregrine (Perry) Gaines Ware – born 1814

married Caroline Broodway

(6) James Henry Ware – born May 25, 1815,

married Margaret C.L. Isabella

Johnson

(See obituary below)

(7) Louisa Catherine Ware – born December 3,

1818 and married Thaddeus

Choice Bolling. Lousia died

October 15, 1910

(8) Edmund Pollard Ware Jr. – born 1821

The names of

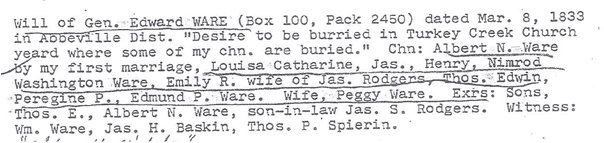

these children are also validated in Edmund’s will, written in 1833. (See below)

Edmund Ware (17 Apr 1833 Abbeville SC Will Book 2-315)

(Abbeville County South Carolina Will Book 2-315)

EDMUND WARE, 17 Apr 1833

"To be buried at Turkey Creek Church where

some of my children are buried"

Son by first marriage: Albert N. Ware.

Son-in-law: James S. Rogers, Thomas Edwin Ware, Peregine P. Ware, Edmund P.

Ware.

Son: Nimrod Washington Ware, James Henry Ware.

Dau: Louisa Catherine Ware, Emily Rogers.

Wife: Peggy.

Wit: Wm. Ware, J. H. Baskin, Thomas P. Spierin

Grave for Louisa Catherine Ware Bolling

The following is the obituary for

Dr. James H. Ware – son of Edmund Ware:

Distinguished Physician Passes Away

at the Ripe Age of Ninety-two years

“Greenville, April 24 – Dr. James H. Ware, one of the oldest

and best known citizens of this city, died at the home of his sister, Mrs. M.L.

Donaldson, this morning at 4 o’clock. Dr. Ware had

been a citizen of Greenville for about 15 years and formerly practiced medicine

in Laurens, Abbeville, and Greenville counties. He was a member

of the secession general assembly, to which he was elected in 18—from Laurens

County.

He was a man of great attainments and a member of the well

known Ware family, being a son of Gen. Edmund E. Ware, who was well known in the

public life of the state a half century ago. He is the

grandfather of Dr. J. R. Ware of this city and is survived by a number of

members of his family in this city and other points.

He would have been 92 years old had he lived until the 26th of this month, and his

practice as a physician covered over 40 years.

There has been much written about the

oldest son of Edmund

and Peggy,

Thomas Edwin Ware.

He not only attained recognition for being a highly successful plantation

owner, and a politician for the state of South Carolina, but also for being the

focal point of a murder trial that occurred in 1853. Thomas married Mary William Jones,

the only daughter of Adam Jones and Jane Williams. Adam “moved to Greenville County where he

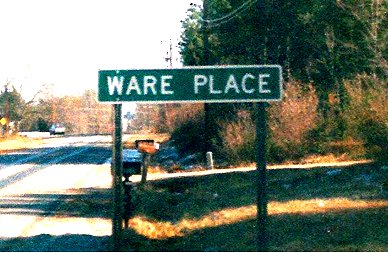

built his residence. It is the dominant residence at a crossroads community

known as Ware Place.”

(Ref. 2546) Thomas Edwin Ware.

He not only attained recognition for being a highly successful plantation

owner, and a politician for the state of South Carolina, but also for being the

focal point of a murder trial that occurred in 1853. Thomas married Mary William Jones,

the only daughter of Adam Jones and Jane Williams. Adam “moved to Greenville County where he

built his residence. It is the dominant residence at a crossroads community

known as Ware Place.”

(Ref. 2546)

Marriage record

"Marriage and Death Notices from Pendleton SC Messenger 1807-1851".

Compiled by Brent H. Holcomb

Issue of July 2, 1834 pg. 45.

Married on Thursday, the 19th inst., by the Rev. Sandford Vandiver,

Mr. Thomas E. Ware, of Abbeville District to Miss Mary Jones, only daughter of

Capt. Adam Jones, of Greenville Dist.

According

to information housed in the ‘Special

Collections and Archives’ at James B. Duke Library in the Furman Institute, “Thomas Edwin Ware (1806-1873) was born to General Edmund Ware and Margaret “Peggy”

Gaines. He was a prominent planter

of Greenville District, and his papers represent an important source for local

and state history. Ware owned and operated Ware Place plantation and mill in the

southern part of Greenville District and employed 102 slaves on his land in

1860. Ware represented Greenville in

the SC House of Representatives during the following terms: 1840-41, 1844-45,

and 1846-47. Then he served in the

state Senate for five additional terms: 1848-49, 1850-51, 1860-61,

1862-63, and 1864. He married Mary Williams Jones,

daughter of Adam Jones (builder of Ware Place).

Thomas was, indeed,

successful. According to a book

titled Greenville: the History of the City and County by Archie Vernon

Huff in 1995, “The Wares moved to the Greenville District and lived with

Jones on his plantation, later known as

Ware Place . . . . He and his

wife joined Brushy Creek Baptist Church

in 1854 after he had a moving religious experience.”

Thomas

was the largest slave

holder in the Greenville district and was considered a

“prominent politician and military man for

the state of South Carolina.”

(Ref. 2546)

Thomas owned about 700

acres of good land on the Saluda River, but a large part of his wealth came not

from farming but from hiring out the vast number of slaves he owned (102

according to the 1860 census). His

plantation, called Ware Place, was known for its beauty throughout the area of

Greenville.

The following

photographs are graciously offered by Bob and Norma Ware who visited the lovely

home. All of the helpful notations

accompanying the photos are also provided by Bob Ware.

Sign for Ware Place

Ware Place

“Ware Place is located about 17 miles from the center of Greenville at the

intersection of US 25 and SR8. It is

not a town, nor is it a community or a village; it is simply four corners of the

intersection. A gas station is

located on one corner, a couple of antique stores on the corner across from it. The Ware Plantation residence is

across US 25 from the stores and a Greenville County fire station on the

remaining corner. Other than that,

the area is typical rural.”

Ware Place – home of Thomas Edwin Ware

“The main view of

the house as seen from US 25”

I am deeply indebted to

Bob and Norma Ware for sharing their photographs, knowledge, and experiences

with me for this book.

“A view of the south side of the house with a partial view of the replacement

kitchen”

“A view of the north side of the house taken from SR 8”

“The north side of the new kitchen”

“The old kitchen that has been moved from the rear of the house to the north

side and is now used as a garage and utility shed”

“View showing the conversion of the old kitchen to the garage”

“Side view and rear view of the old kitchen.

It appears that it was a large structure in its self.”

From the

beginning of their marriage, Thomas and Mary resided in the same house with her

parents. Mary was an only child and

obviously close to her mother. It

would seem that relations with her father were often difficult, however. It was later reported that

“Col. Ware lived in the greatest harmony

with [him], and never had any difficulty with him, though he did not approve of [his] conduct towards his family.”

(Ref. 2556)

The situation only became more stressful after Mary’s mother died, and

“Col. Ware was ever a peace maker between

[Mary’s father] and his wife.”

(Ref. 2556)

In 1853, the situation

escalated to a horrible level.

Thomas and Mary decided to leave the plantation and move into Greenville to

avoid further problems with her father, who was now drinking more and more. On the day of their departure, there

was a major confrontation. An

intoxicated Captain Jones attacked Thomas in a fit of rage with a pair of iron

fire tongs. Thomas ended up pulling

out a gun he owned and fatally killing his father-in-law. He was arrested for manslaughter.

An excerpt of the trial of Thomas Edwin Ware, taken from a newspaper titled The Southern

Patriot in Greenville, South Carolina (printed on Thursday morning April 21,

1853), gives vivid details of the many testimonies brought forth. The physician who examined both men

after the shooting gave the following quote in an effort to show that Thomas had

acted in self-defense.

“The blow was aimed, as he thinks, at Ware’s head:

Ware’s arm, one of the bones broken;

[doctor] thinks if the whole force of the blow

had been received on his head, it would have produced fracture of the skull and

most likely death as a consequence; had attended Ware’s arm; paralysis of the

fingers; nerves injured; may never recover use of the fingers . . . .”

(Ref. 2556)

In a somewhat shocking

turn of events, Thomas was convicted on the charge of manslaughter but given an

incredibly light sentence. In fact,

he received a full pardon one week later.

The following article, written about this interesting story, has been

graciously and generously offered by the author, Norma Ware.

WARE PLACE

by Norma Ware, English 9, Writing Memoir,

Autobiography, and Family History, April 15, 1997

Below is the announcement of the pardon for Thomas Edwin Ware

(Ref. 2556)

Thomas and Mary continued to live at Ware

Place for the next 20 years. It was

here that they had started their family and raised their children - the

grandchildren of

Edmund and Margaret and great grandchildren of

Nicholas

and Peggy. The nine children were:

Mary Pauline,

James Edwin, Anna

Louisa, Margaret Jane,

Edmund James,

Albert Williams, Thomas Jr.,

Clarence Eugene,

Mary, and George Barstow.

1. Mary Pauline Ware

(born March 25, 1836) wed James H. Arnold on April 22, 1858,

at her parent’s home, Ware Place.

She was called Pauline as can be seen in the following news clipping.

Marriage and Death Notices From the Up-Country of South Carolina as taken from

Greenville newspapers 1826 - 1863

compiled by Brent H. Holcomb

Married on

Thursday evening, the 22nd ult., by Rev. Mr. Wells, Mr. James H. Arnold of

Laurens District, to Miss Pauline Ware, of this district. (May 6, 1858)

2. James Edwin Ware

(February 15, 1838)

He died on December 1, 1854, at the age of 16.

3. Anna Louisa Ware

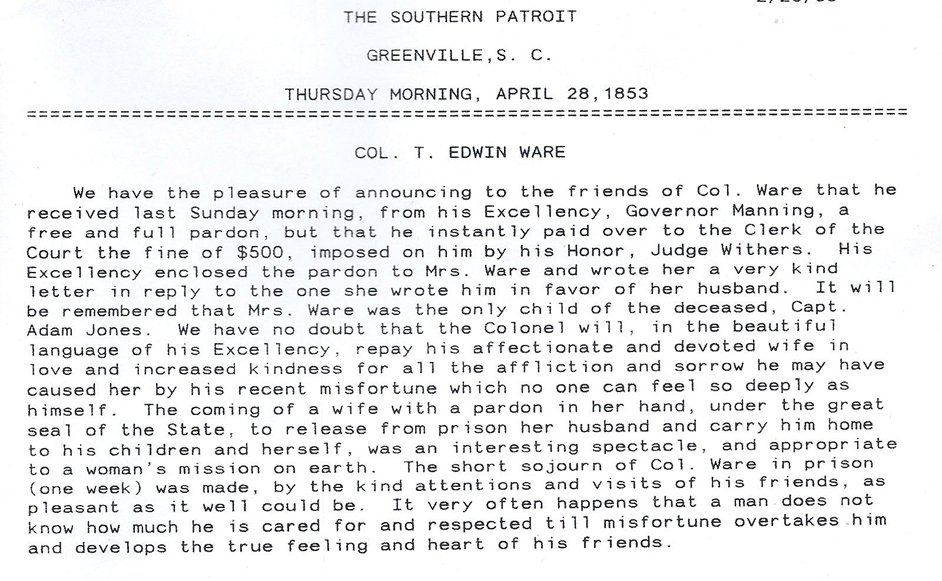

(January 29, 1840) married Major Garland Mitchell Ryals

on October 25, 1870. Major Ryals was

Provost Marshal to General J. E. B. Stuart during the Civil War. Below is an oil painting done by Ron Lesser in 2003, titled

The Shelling of Carlisle -- July 1-2. Major (then Lieutenant) Garland Ryals

(husband of

Anna Louisa Ware) is one of the soldiers depicted in the painting.

In foreground, left to right, Major Andrew Reid Venable, Major General Jeb Stuart, Lt.

Garland Mitchell Ryals, Major Talcott

Eliason

![[graphic]](http://www.waregenealogy.com/Images/NNNH157.jpg)

Garland Mitchell Ryals

Garland married

Anna Ware on October 21, 1870, and they

had four children. Garland died in

1904 from complications due to diabetes.

Anna Ware Ryals died May 17, 1912.

Grave marker for Garland Mitchell Ryals and

Anna Louisa

Ware Ryals

4. Margaret Jane Ware

(May 3, 1842) was born at Ware Place (as all the younger

children were). She only lived six

years, dying in December 1848.

5. Edmund

James Ware (December 19, 1845) In June 1864, he was mortally wounded

in Virginia during a battle. His

body was brought home and interned at the old place.

6. Albert Williams Ware

(September 29, 1847) Albert

wed Anna Lucy Watson on December 21, 1870, in an Episcopal church in Greenville. The couple had nine children: (1) Lucille, (2) Ethal, (3) William,

(4) Irvin, (5) Alicia, (6) Minna, (7) Mitchell, (8) Hext, and (9) Edwin. Albert died March 31, 1916.

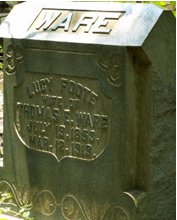

7. Thomas E.

Ware Jr.

(August

20, 1849) married Lucy H. Foote in 1870, and they had eight children: (1)

Edwin, (2) Eugene, (3) Oliver, (4) Mary, (5) James, (6)

Ellen, (7) Simpson and (8) Charles.

Thomas Jr.

took over management of Ware Place when his parents died, and he was the last

member of the family to live there before it sold.

Thomas E. "Salt" Ware (1849-1904) –

son of Thomas and Mary

Both

Thomas Ware

Jr. and his wife, Lucy Foote Ware, are buried in the family cemetery

on Ware Place, along with other members of the family. The three small gravestones at the

bottom of this page are for some of their children who, clearly, died young.

Lucy Foote Ware – wife of Thomas (Salt) E. Ware

Ellen

Ware died at age 5; James Sidney Ware died

at age 3; Simpson Ware died at age 2

8. Clarence

Eugene Ware

(January

27, 1851) had the unusual nickname of “Coon” Ware. He married Mary Elizabeth Davis, and

they had the following children: John,

Martha, James, Mary, Anna, and Clarence Jr. Clarence

died August 7, 1917.

Grave for

Clarence Eugene "Coon" Ware (1851-1917)

Son of Thomas and Mary Jones Ware

9. Mary Ware

(November 26, 1854) wed William Lee Coleman, Jr., on January 10, 1877, and they

had the following five children:

Marie, William, Lewis, Edith, and Garland.

Mary died on June 28, 1920.

10. George

Barstow Ware

(March 1,

1859) He was the last child

for Thomas Edwin Ware Sr. and Mary.

Thomas Sr. and Mary put the past behind

them after the death of Adam Jones.

With the exception of their last two children, all the other offspring were born

prior to the shooting. Only baby

Mary and George would have grown up in a house without feeling the tensions that

existed between Mary and her belligerent father.

Thomas accrued great wealth in his lifetime and stayed very active in

politics.

(Ref. 2555)

There is a graveyard on Ware Place, and one ancestor wrote

that Thomas “and his wife (Mary Catherine Jones) are buried at the

site of the Ware old home place along with several family members. The Ware

Family Cemetery is very run down and many of the graves been vandalized . . . .

This graveyard is in the woods and unkept!”

(Ref. Web)

Thankfully, there has been an effort in

recent years to restore and take better care of this historic spot. Thomas died in 1873, and Mary died in

1885.

Marker for Thomas Edwin Ware Sr. 1808

-1873 and Mary W. Jones Ware 1810 -1885

Edmund and Margaret Ware prospered on their Saluda River property. The following two documents give a

good indication of how this son of Nicholas

and Peggy obviously stayed active in South Carolina civic affairs.

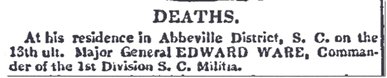

Edmund had earned the rank of major general during his military service in

South Carolina. At one point, he was

the commander of the 1st Division of the South Carolina Militia. Information

attached to The Mills Atlas Map made in 1820, for Abbeville District, refers to "General

Ware's Mill" on Saluda River, and Wanda

DeGidio validates his rank in her writing “General Ware was buried in Turkey Creek

Cemetery.”

(Ref. 379) His marker is no longer visible in the cemetery, but the church documents let us know that he “died on April 13, 1833, aged 53 years.” Margaret only lived one year

longer and her tombstone reads:

“Margaret Peggy Gaines Ware: death March 25, 1834 age 46 - wife of

Edmund.”

1833 Newspaper

Last Will & Testament for

General Edmund Ware

In 1814, Nathaniel

married Sarah Percy Ellis, the widow of Judge John

Ellis who died in 1808. Sarah had

two children (Thomas and Mary Jane) by her first marriage. She was from a prominent Southern

family, known for great affluence and social connections. Sadly, however, they were to be

remembered for another reason as well.

Several family members “had

a vulnerability to mental illness” . . . a fact which would haunt Nathaniel

for the rest of his marriage.

Sarah was “very young when left a widow by Colonel Ellis,” and Nathaniel was not only handsome, but a “man of profound learning and well versed

in science, particularly in Botany.”

He also was “a man full of eccentricities and naturally very shy and reserved in character . . . a

philosopher of the school of Voltaire, a fine scholar, with a pungent, acrid

wit, and cool sarcasm, which made him both feared and respected by those brought

into collision with him.”

(Ref. 2552)

Nathaniel had attained the rank of major

while serving as a military aide to the governor in 1812, and had

“gained appointment to the Governor’s

Legislative Council, by order of President Madison.”(Ref.

2554)

He was a man with high ambitions for the

future and was “on the way to the top.”

(Ref. 2554)

Their future looked very bright.

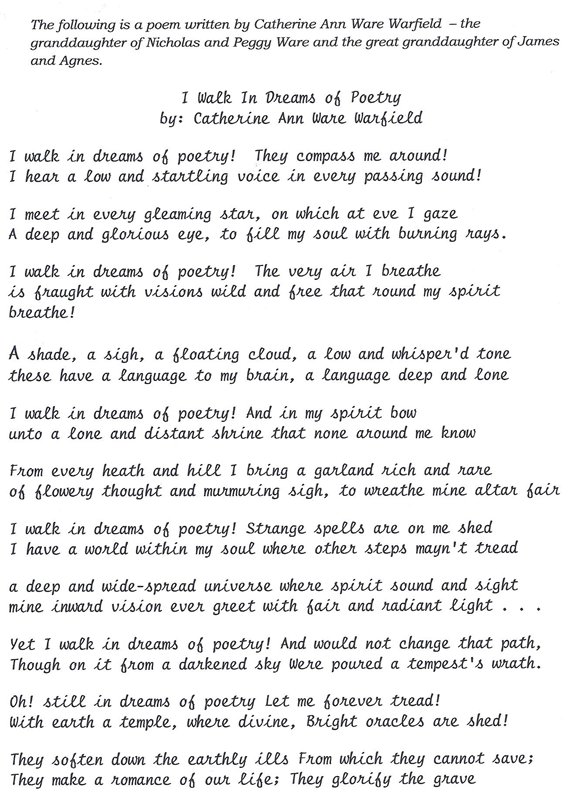

In addition to Sarah’s two children by her first marriage, another baby joined

the household in Natchez, Mississippi, on

June 6, 1816. Nathaniel and

Sarah named their first daughter Catherine Ann Ware. The little girl would later be described as having “the Percy eye - dark gray with black lashes and a forceful

chin.”

(Ref. 2545)

Catherine Ann Ware

As she grew older, she “stood very erect”

at five foot, three inches and “had hair

black like her mother Sarah’s and half sister.”

(Ref. 2545)

Author Ida Raymond described her as having

“soft dark-gray eyes, radiating emanations

from a spirit so warm and so strong – eyes so full of vitality, both mental and

sensuous.”

(Ref. 2552)

Raymond gave an even more in-depth

description later: “Her eyes are . . . shadowed by black lashes, her brow is beautiful; nose, straight, fine and

delicate . . . her appearance is striking and attractive; genius is stamped in

every lineament.”

(Ref. 2552)

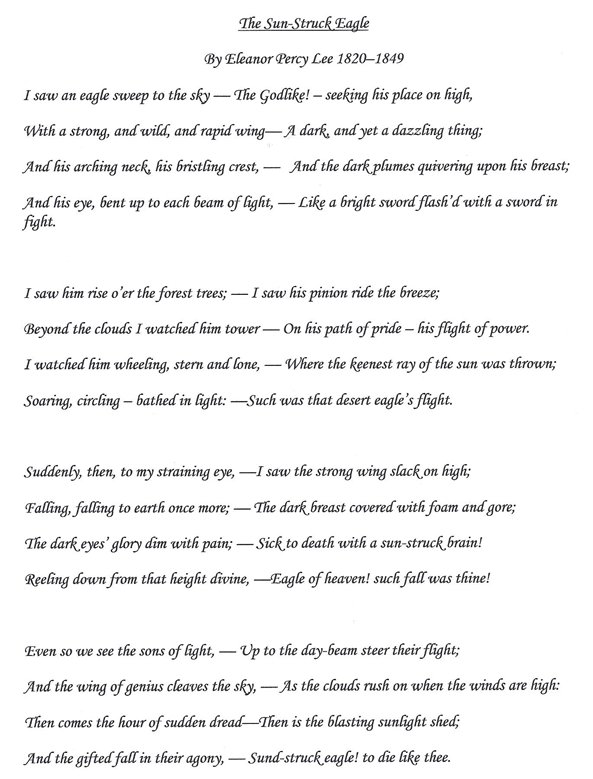

Three years after Catherine’s birth, in

1819, Nathaniel and Sarah had their last child, Eleanor Percy Ware. Eleanor was described as “a beautiful child” with a “brilliant complexion . . .

a picture to see; her eyes were as blue as

heaven, her features statuesque, her hair black.”

(Ref. 2552)

Where Catharine was thought to be “shy and sensitive,” Eleanor was

“self-reliant, gay; dancing like a

sunbeam.” (Ref. 2552)

The siblings were incredibly close, and as Raymond wrote, “the love between these sisters was peculiar and beautiful . . . they absolutely seemed to have

but one soul. . . . Nothing could be

more perfect than the confidence and friendship between them.”

(Ref. 2552)

A large reason for the closeness between

the two girls was probably due to the sadness they shared throughout their

childhood. Tragically, their mother,

who “was 39 when Eleanor was born and

suffered from post-partum depression following the birth . . . never fully recovered.”

(Ref. 2552)

The mental problems that dominated Sarah were a family legacy. The father whom she adored, Charles

Percy, “was a man of cultivation, taste,

and refinement, but of a melancholy nature, which, after the death of his third

son, Charles, settled into the gloom of mania.”

(Ref. 2552)

There seemed to be nothing Charles could do

to alleviate his depression so, sadly, he resorted to suicide. Sarah was only 10 years old when her

beloved parent tied a large iron kettle around his neck “and plunged to his death in the black waters of Buffalo Creek, thereafter called Percy Creek.”

(Ref. 2558)

With eerie similarity, Sarah Percy Ware’s

descent into mental illness was equally steady and unrelenting.

As young children, one can only imagine the trauma both Percy sisters endured

while watching their mother suffer.

It was said that when they went to visit her, “she never was able to recognize them. Mrs. Ware retained her health, and

some remains of former beauty. Her

hair, though snow-white, still swept almost to the floor as she stood erect, her

hands and arms were models for a sculptor; she noticed very little, sometimes

would open a book but never read any. . . . She

never recognized her husband, and he rarely ever saw her. . . .

She would weep sometimes for her baby

‘Ellen’ but would repulse the caresses of her weeping daughter, who would often

try to make her mother understand who she was.

These attempts however only distressed the poor lady.”

(Ref. 2552)

Mental illness was greatly misunderstood at this time in history, and it must

have been painful for their father to try and explain to his daughters the

reason why their mother “liked to paint or

draw flowers and birds on the walls, yet she would never use pen or brush on

canvas or sketching pad.”

(Ref. 2558)

Nathaniel, who “had once entertained hopes for a grand political future,” came to realize that those dreams

were now unattainable.

(Ref. 2558)

He

was at a loss as how to deal with Sarah’s condition. A man not prone to lavish displays of

affection or frivolous conversation under the best of circumstances, some people

saw his reserved personality as possibly contributing to Sarah’s state of mind. Others saw him as an incredibly

supportive husband and

loving father. The following is how

one author in the 1800s summed up Sarah’s situation:

With Sarah, “the family proclivity inherited from her father

declared itself, and the charming, attractive young woman never recovered her

reason. . . . Major and Mrs. Ware

were then living near Natchez. There

was the loudest expression of

sympathy and regret on the part of her many friends, by whom Mrs. Ware was

greatly beloved, but after trying every medical suggestion that the South could

afford, Major Ware was compelled to take his suffering wife to Philadelphia for

better advice - her two children by her first marriage were already there. . . . Now the father had to take charge of

his two helpless little girls, so sadly deprived of their mother's tender care. He was passionately devoted to his

little daughters, never content to have them away from him; and he did the best

he could for them. They had wealth and friends, but it was lonely for the little

things, wandering about from place to place, as their father's wretchedness led

him to do, in his restless, weary life . . . .

[They were] never long

separated from the stern, peculiar

scholar, whom they could not comprehend, except in his intense tenderness and

earnest anxiety to bring them up as lovely, refined ladies should be educated.”

(Ref. 2552)

Sarah Ware “remained in the hands of physicians in Philadelphia for eleven years.”

(Ref. 2554) Nathaniel spared no expense in trying

to get her help because records show

“she

was the highest-paying patient, and the only one accompanied by a resident slave, at

the Pennsylvania Hospital, then one of the few institutions that clinically

treated the mentally ill.”

(Ref. 2552) It did not lessen the emotional

toll on the children, however.

Nathaniel

found himself in the difficult role of a single parent. Knowing how important education was

to himself when growing up, it is not surprising that he wanted both his

daughters to have the best opportunities for learning that he could offer them. The girls

“attended the

academy of Mme. Aimée Sigoigne, an émigré from Haiti.

Her French-speaking school attracted many upper-class Southerners and

Philadelphians.” (Ref. 2552)

In addition,

Nathaniel, who used travel as a way to deal with his own sense of loss and

sadness, “frequently took his young

daughters with him.”

(Ref. 2552)

In an interesting work, titled Prince

Among Slaves, and produced by the Cultural Legacy of Enslaved Africans, we

find a little known side of Nathaniel’s character. The following is an excerpt from this

article found on the web:

“In April, 1828, as Abdul Rahman boarded the steamship Neptune and watched Natchez fade into the

distance for the last time, it was surely a bittersweet parting. His own freedom in hand, Abdul Rahman

carried with him the heavy knowledge that his children's tether had not been

cut. He was accompanied on his

journey by one of Foster’s wealthy planter friends,

Nathaniel A. Ware. One of the luminaries of the colonial

South, Nathaniel A. Ware was a public official in Natchez and one-time acting

governor of Mississippi. As the father of

poets Catherine Ann Warfield and Eleanor Percy Lee, he headed what was to become

a Southern literary dynasty. [. . . . ]But as Ware accompanied the freed slave on his

journey from the land of his servitude in 1828, the Confederacy, secession, and

the unstoppable tide of abolition had not yet appeared on history's stage.

On this day, Ware was an official of the

status quo who stayed by Abdul Rahman's side until the two arrived in Washington

D.C. Here in the seat of the government

which had helped secure his release, the Prince parted company with Ware, who

went on to Philadelphia. Months later, as Abdul Rahman passed through

Philadelphia on his northern tour, the two met again.

Perhaps it was the time Ware spent in the

city where the Declaration of Independence, proclaiming the equality of all men,

had been heralded by the Liberty Bell, or perhaps it was the time he spent with

Abdul Rahman, but Ware stepped outside his expected role.

A slave owner himself, he donated $10

(which in those days was real money) to the fund to free Abdul Rahman's

children.”

Nathaniel was clearly an enigma: a

Southerner with a sympathetic heart- - a devoted husband who developed a

withdrawn demeanor - - and a father who was loving, yet often aloof.

Both daughters showed great literary aptitude at an early age. Eleanor wrote her first poem at the

age of 11, and Catherine Ann was soon creating her own verses. Their writing was often moody and

dark, however; probably reflecting their sadness over their mother. Nathaniel encouraged them greatly in

their endeavors, even going so far as to commission publishers for them.

In 1831, Nathaniel “moved Sarah back to Natchez, where she was under the care of her son Thomas George Ellis, from

her first marriage.

Thomas George Percy Ellis

Catherine

Anne and Eleanor would visit their mother every summer when home from school.”

(Ref. 2552)

Even though she was among family,

Sarah did not rally. One of Thomas’ daughters, Sarah Percy

Ellis, recalled her grandmother as “hopelessly

melancholy, possessing everything that the prestige of birth, and rank, and

wealth could give; but the ‘skeleton in the closet’ was always there, and for

years this dreadful thought pursued her.”

(Ref. 2552)

The whole family was well aware of the

inclination for mental instability, and it must have brought terrifying

questions. Thomas’ sister, Mary

Jane, had also “for long years suffered .

. . under eclipses of reason” and her

“slip into insanity in 1838” was another blow to a family besieged by grief.

(Ref. 2554)

In his own way of dealing with the situation, Nathaniel made it clear that

Sarah’s condition was not to be talked about or discussed – a common reaction

for the times in which he lived, but also an isolating factor for his confused

and suffering children.

Both Eleanor and Catherine found an outlet for their emotions by “translating gloom of mind into poetry and fiction.”

(Ref. 2554) They hated the times when their

father had to travel alone and felt abandoned when he left. Even though he was not a

demonstrative man, they adored him and craved his attention and affection. In 1836, their mother, Sarah Percy

Ellis Ware, died at the age of 56 - finally achieving the peace that alluded her

most of her life. Thus would end

Nathaniel’s 22 years of wedlock. Not

surprisingly, he never chose to remarry.

By the time of Sarah’s death, Catherine had

been married for three years. “At age sixteen, on

January 3, 1833, Catherine Ann wedded Robert Elisha Warfield, a son of the prominent Lexington,

Kentucky physician and Thoroughbred breeder . . .

the Warfield family had founded the

Lexington Association Race Course.”

(Ref. 2554)

The couple settled in Kentucky.

Marriage Notes for Robert Elisha Warfield and Katherine/Catherine Ann

Percy Ware:

Record of a marriage of Elisha Warfield,Jr., of

Lexington, KY, to Miss Catherine Ann Ware of Philadelphia. Married in

Cincinnati, OH, 28 Jan 1833

Nathaniel’s youngest daughter, Eleanor,

waited until she was older before marriage.

On May 25, 1840, she wed the cousin of Robert E. Lee, William Henry Lee.

“Her father settled the couple with a large dowry from

Eleanor's mother's legacy: ‘a large

plantation in Hinds County, Mississippi, with about 85 slaves, assessed in 1838

at the value of $122,000.’"

(Ref. 2554)

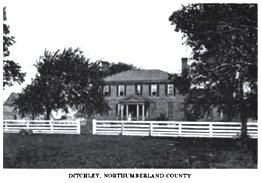

Their beautiful estate was called

‘Ditchely,’ and although Eleanor died earlier, William Henry Lee resided there

until his own death in 1874.

Ditchley

Throughout their lives, the two sisters

shared their common love of writing.

They were both competitive and supportive. “Ellen had the gift of total recall and

could recite without error any poem that she fancied. Catherine, however, had greater

sensitivity and inventiveness than her sister, but they liked to think that

their talents complemented each other’s.”

(Ref. 2554)

Nathaniel was, with good reason, very proud of both of them, and the girls were

“gratified that their father thought their

work publishable.”

(Ref. 2554)

It would seem that both literary talent and tragic mental illness would continue

to afflict the family, however. “After their mother's death, the sisters

next suffered the death in 1844 of their half-sister Mary Jane Ellis LaRoche

(who appeared to have suffered from post-partum depression and lingering mental

illness for several years) and later their half-brother Thomas Ellis” as

well.

(Ref. Wikipedia)

Thomas died at the young age of 33.

Although not as severe, Eleanor seemed to

have inherited the family predisposition for depression. After the loss of Mary Jane and

Thomas, her zest for life declined. “Of the two sisters, Catherine was the more accomplished and much more prolific poet.”

(Ref. 2554)

In fact, sometime earlier, Eleanor “gave

Catherine the editing lead for their joint volumes. . . . In the summer of 1849, while at the

resort of Mississippi Springs, she complained of melancholy [our word for

depression].

She died of yellow fever during an

epidemic that summer, at the age of 30.”

(Ref. 2554) Eleanor

had only been married nine years.

Nathaniel’s oldest daughter, Catherine,

appears not to have been as emotionally fragile as her other family members,

although even Catherine had a bad bout of depression. “After Eleanor died of yellow fever in 1849, Warfield ceased writing for several years, as she

was stricken with melancholy.”

(Ref. Wikipedia)

She was able to overcome her natural grief, however. In “the mid-1850s, Catherine was encouraged

to start writing again by her niece Sarah Ellis, already a successful novelist. In 1860 Warfield published

anonymously as ‘A Southern Lady’ [a book titled]

The Household of Bouverie, a

gothic fiction in two volumes. It

achieved great popular success. . . .

After the Civil War, Warfield published eight more novels, all under her

own name. The two most popular were

Ferne Fleming (1877) and its

sequel The Cardinal’s Daughter

(1877).” (Ref.

2552)

On the home front, Catherine and Robert were busy raising their six children in

Kentucky. It is hard to know how

much satisfaction Catherine gained from her writing success since “remembering a cheerless childhood under

the supervision of austere governesses and a distant father and, above all,

denied a mother’s love, Catherine early had learned to hide her feelings.”

(Ref. 2558) It would seem, however, that

she gained great comfort from her Catholic religion because she

“recognized that order, structure, hierarchy, and a moral imperative could challenge depression.”

(Ref. 2554) Her faith gave her hope and a way to

reconcile loss and pain. The

following are some of her books that were published (The Household of

Bouverie probably her most famous).

Catherine Ware Warfield died in 1877 and is buried in Kentucky.

Catherine Ann Ware Warfield

Sarah Anne Ellis, cousin to Eleanor and Catherine, would also become well known

for her literary accomplishments.

Her style leaned more toward historical writing, however, and she did not shy

away from political issues. After

her husband (Samuel Dorsey) died, Sarah invited Mr. and Mrs. Jefferson Davis to

her home called ‘Beauvoir’ in Biloxi, Mississippi. The former president of the

Confederacy was struggling in his efforts to write his memoirs. With no children or husband to tend

to, Sarah devoted herself to helping Davis with his autobiography.

“She transcribed notes, took dictation, corrected prose, and offered

advice about style and organization.”

(Ref. 2554)

When she realized, in the winter of 1877,

that she was dying of breast cancer, Sarah changed her will, making

“her sole commitment to Jefferson Davis’s

ease in retirement.”

(Ref. 2554)

As “the only heir of her fortune,” he now became the

owner of her beautiful waterfront property of Beauvoir.

Jefferson Davis

;

Beauvoir

Sarah

Ellis Percy Dorsey;

Beauvoir 1901

Photo

courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

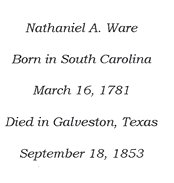

Major

Nathaniel Ware lived to see some of his oldest daughter’s works

published, but he died before Catherine really reached her full height of fame. Ever traveling, he had made several land investments during his

lifetime - - one near Galveston, Texas.

It was there that he died in 1856 of yellow fever. Catherine erected a monument for him

in Kentucky to honor his life.

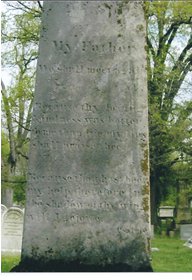

Following photos taken by James and Judy Ware 2012

The inscription reads:

My

Father - We shall meet again

“Because thy loving kindness was better to me than life, my

lips shall praise thee.

Because

thou hast been my help, therefore in the shadow of thy wings will I rejoice”

There

is more writing at the very bottom of the stone but it is too difficult to make

out at this time.

With the birth of

Nathaniel Ware,

Nicholas

and Peggy Hodges Ware had completed their family.

They were now able to chart their own course in making a mark on this now

‘united’ nation. For several

reasons, Nicholas decided to relocate his family to South Carolina.

During the 1700s most of South Carolina was occupied by the Cherokee Indians.

Understandably, these natives were not overly thrilled with the constant press

of white settlers encroaching on their lands.

There was not only conflict with the colonists but between different

Indian tribes as well. In 1758, when

Nicholas was 19 years old, Cherokee “warriors

accompanied Virginian troops on a campaign against the Shawnee of the Ohio

Country. During the expedition, the

[Shawnee] enemy proved elusive, while

. . . the Cherokee stayed, but dwindled.”

(Ref. Wikipedia) It is very possible, because of his

age, that Nicholas was part of this Virginia military unit sent to the area.

It was not long before the Virginians and the Cherokee turned on each other and

began fighting. The situation would

become quite grim.

The following

excerpt was taken from a work called “The Scotch-Irish, and their First

Settlements on the Tyger River, and Other Neighboring Precincts in South

Carolina, a Centennial Discourse” which was delivered at Nazareth Church,

Spartanburg District, South Carolina on September 14, 1861, by George Howe.

“But now came a season of dreadful trial to

these devoted people. The Indian tribes,

which almost surrounded them, became incensed against the whites, and rose in

arms to destroy them. The inhabitants of

Long Canes, in Abbeville, fled for refuge to the older and more settled parts of

the country. A party, of whom Patrick

Calhoun was one, who were removing their wives and children and more valuable